Today is International Men’s Day, so it felt right to post an essay I wrote exactly 10 years ago on masculinity in Ernest Hemingway’s short story “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” (1936). Back then I took the course “Modernism and Literature in the United States” at the University of Barcelona, where I was inspired by Prof. dr. Àngels Carabí Ribera, who focussed her research on Masculinity Studies. In literature and film at the time of the interbellum, women were often depicted as the evil femme fatales who corrupted men. History seems to repeat itself, not only in the political shift to the right after a financial crisis, but also in the rise of toxic masculinity as a fearful reaction to women’s emancipation.

“It’s a man’s man’s man’s world” claims the famous song by James Brown (1966), but were men always as strong as society charged them to be? During some episodes in history, masculinity showed its paces. The Roaring Twenties were one of these turning-points for patriarchal society, and Francis Macomber, protagonist in Hemingway’s short story “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” (The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories, P. F. Collier & Son, New York), embodies this feminised twentieth Century male perfectly.

To understand the impact of this sudden change, we first need to know how men were supposed to behave during the proceeding decades, or, how masculinity was and is still defined. According to Michael Kimmel (CARABÍ, Àngels, and ARMENGOL, José M. (2005). Debating Masculinity (DVD), Audiovisuals. Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona.), feminism defined gender as a system of relationships of power. As anthropologist David Gilmore says (CARABÍ, Àngels, and ARMENGOL, José M. (2005). Debating Masculinity (DVD), Audiovisuals. Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona.), masculinity had always been dominating in enforcing this power. Until now, the majority of cultures are still patriarchal, i.e. seeing the role of women in public space as complementary and inferior. Lynne Segal once depicted masculinity by the following list of negations:

“Masculinity is not feminine, not ethnic, and not homosexual.” (SEGAL, Lynne (1997) Slow Motion. Changing Masculinities. Changing Men, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, N. J.)

After years of being the current charges for men, these norms suddenly staggered. Circumstances are the 1920s, United States. World War I had just come to an end, and the economy was flourishing, while new technical inventions improved one’s daily comfort. Man was no longer the sole designer of an achieved product. He was but a cog in the machine, meaningless among the other workers, in an industry of which he could not grasp the whole extent. This was a decade of great prosperity, but nonetheless, of sordid decadence as well. After war had shattered all faith in the innate goodness of mankind, an age of careless individualism took off. With all the 19th century values of the United States vanished, and its inhabitants being totally unsettled in their new urbanised environments, they were torn between America and Europe, only to discover that there was no place whatsoever where they could belong.

Yet, one of the most thorough changes might be the newly gained liberty of women. While their husbands had been fighting at the European front, they had kept the national economy turning by taking on jobs out-of-doors, and therefore, had gradually entered the public space, previously the field of men only. This new independent women, known as “the flapper“, was provoking in appearance as well as behaviour. Her hair was cut short, gowns dared to show knees, and stiff corsets were done away with. Despite this boyish look, women had never been more openly seducing, as they smoked, drank (in spite of the 1919 to 1933 Prohibition), and shamelessly punned on sexuality. The flirting naughtiness of the period is best caught in the words of actress and sex symbol Mae West, stating that “[i]t’s not the men in your life that matters, it’s the life in your men”(RUGGLES, Wesley (1933) I’m No Angel, Paramount Pictures, Paramount Productions Inc., USA.). Margot has no shame either in checking the new men she meets, like the hunter Wilson. “‘You know you have a very red face, Mr. Wilson,’ she told him and smiled again.” (Hemingway, 459) Wilson, for his part, remarks upon the flapper that “[t]hey are (…) the hardest in the world; the hardest, the cruellest, the most predatory and the most attractive and their men have softened or gone to pieces nervously as they have hardened”. (462)

One can easily understand that the new liberated women were quite a threat to men. Conservative repercussions quickly followed, and women were frequently depicted as the cause of men’s troubles by famous authors of the time. Hemingway, as Minter (MINTER, David L. (1994) A Cultural History of the American Novel, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 137-145) states, “saw virtually every situation and relationship as a contest waged with some threatening ‘other’ (…). He characteristically thought of families as destructive scenes (…)”. Therefore, a predominating theme in his novels was the clash “between different genders, classes and races (…)”. Watson (WATSON, James Gray. (1974) “‘A Sound Basis of Union.’ Structural and Thematic Balance in ‘The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.'”, Fitzgerald/Hemingway Annual, 1974, 217) also states that Hemingway’s “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” deals with sexual conflict; and that “[b]oth Francis, by his cowardice, and Margot, by her infidelity, (…) threaten the identity of the other”.

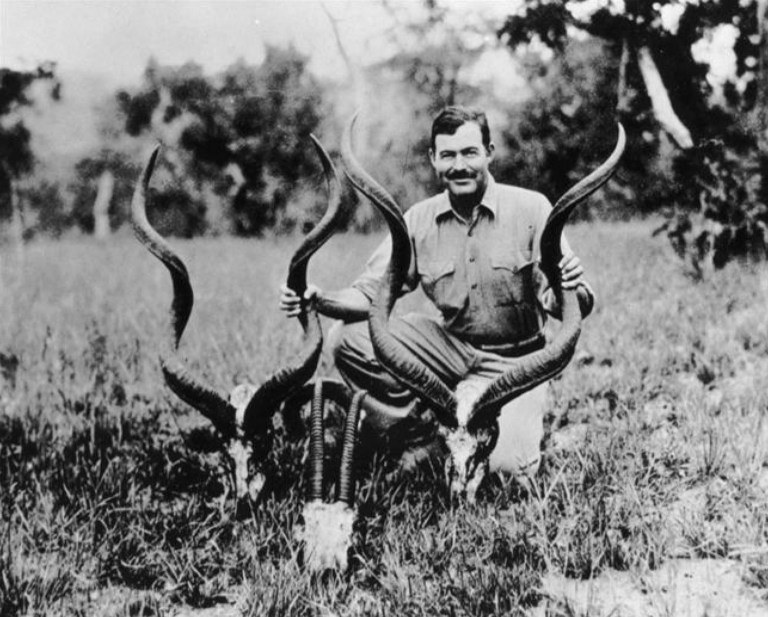

Normally, Francis Macomber, being a male, upper middle class, heterosexual American man in his thirties, would have been the ideal dominant male. His unsatisfactory sexual capacities, however, as a man castrated by his own all too dominant wife, make him a very vulnerable and insecure creature. David Gilmore (CARABÍ, Àngels, and ARMENGOL, José M. (2005). Debating Masculinity (DVD), Audiovisuals. Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona.) states that in every society, different tests of masculinity exist. Because there is no clear mark for masculinity – as opposed to femininity where a girl’s first periods serve as a transition event– men feel the need to prove their masculinity to stop feeling insecure. Francis thinks a way of displaying his manliness to himself, his wife, and other men, is to go on a safari to Africa and shoot some animals. The fact that he, as one of the few white men, is served by black gun-bearers, validates Lynne Segal’s claim that, to remain in power, the white heterosexual man tries to diminish the value of other cultures by maintaining the stereotypes of the dominant Western culture (SEGAL, Lynne (1997) Slow Motion. Changing Masculinities. Changing Men, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, N. J.).

Yet, the gained effect was the total opposite of what Francis had hoped for, as he only proved his cowardice during the lion hunt. Nervously, he tried by all means to avoid the confrontation with the animal, and when it finally attacked, he ran away in panic.

“It was there exactly as it happened with some parts of it indelibly emphasized and he was miserably ashamed of it. But more than shame he felt cold, hollow fear in him. The fear was still there like a cold slimy hollow in all the emptiness where once his confidence had been and it made him feel sick”. (Hemingway, 464-465)

The public contempt that follows emphasizes his incompetence.

Instead of comforting her husband, Margot stresses his failure even more by ridiculing him on every possible occasion. She refuses to talk to or even look at her husband, increasing his embarrassment by her own low regard for him. She diminishes every progress he makes: “‘Did you shoot it Francis?’ she asked. ‘Yes.’ ‘They’re not dangerous, are they?'”. (Hemingway, 463) To demonstrate his complete powerlessness, she even cheats on him, knowing, as the following conversation shows, he would never feel confident enough to leave her: “‘You think that I’ll take anything.’ ‘I know you will, sweet.'” (Hemingway, 476) As Sugiyama (SUGIYAMA, Michelle Scalise (1996) “What’s Love Got to Do With It? An Evolutionary Analysis of ‘The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber'”, The Hemingway Review, 1996, v 15, n 2, 23) says, “he ‘tolerates’ her behaviour (…), because he does not have the social skills necessary to acquire a younger, more beautiful wife”.

“His wife had been through with him before but it never lasted. He was very wealthy, and would be much wealthier, and he knew she would not leave him ever now. (…) If he had been better with women she would probably have started to worry about him getting another new, beautiful wife; but she knew too much about him to worry about him either. (…) Margot was too beautiful for Macomber to divorce her and Macomber had too much money for Margot ever to leave him.” (Hemingway, 474-475)

The sense of domination shifts completely, however, when Francis does shoot down a buffalo. His triumph can be seen through the whole last pages of the text: “For the first time in his life he really felt wholly without fear. Instead of fear he had a feeling of definite elation”. The sudden improvement in his hunting abilities, and the boost of confidence he gains by it, are to Margot, as Sugiyama says, “a threat, due primarily to his knowledge of her infidelity.”(22) “Margot has ample reason to fear that her newly-confident husband will leave her for a younger woman.” (26) She sees the change in her husband:

“‘You’ve gotten awfully brave, awfully suddenly,’ his wife said contemptuously, but her contempt was not secure. She was very afraid of something. (…) ‘You know I have,’ he said. ‘I really have.’ ‘Isn’t it sort of late?’ Margot said bitterly. Because she had done the best she could for many years back and the way they were together now was no one person’s fault. ‘Not for me,’ said Macomber.” (Hemingway, 486)

Macomber had regained his lost confidence, and, in consequence, his lost masculinity. As Wilson points out sadistically to Margot, while letting her beg in her unstable position to stop taunting her, “‘He would have left you too.'” (Hemingway, 488) The female part was again reduced to the dependent pleasing of males who could give a prospect of material wellbeing, while man once more used and misused his patriarchal authority. It would take until the 1960s before this early glimpse of female independence would be fully established in the feminist movements. Only one week ago, a Saudi Arabian imam was preaching on how to best hit your wife when she refuses to obey you (SAHUQUILLO, María R. (2007) “Un imán saudí muestra en TV cómo pegar a una mujer”, El Pais), which proves that men are still restoring their decreased dominance, for the most part by means of domestic violence.